Time management is a big concern for new law students. Here is a sampling of questions I hear each year:

- Is it normal to take 3 hours to read for class?

- Class prep takes so long, when am I supposed to fit in reviewing and this outlining thing I keep hearing about?

- How can I possibly fit it all in?

- What do you mean prioritize sleep? I’ve got to read.

- Etc., etc., etc.

If you’ve never worked a full-time job, the first semester of law school is going to be rough on the stamina front. (Mad respect to those of you who got through college working multiple jobs and what-not, but doing the same chair-bound thing for 40+ hours per week mostly during business hours is a different type of energy spend.) If you’re coming to law school from a degree program that didn’t assign a lot of reading and papers, the first semester of law school is going to be rough on the maintaining attention while reading front. If you’re coming from a degree program that didn’t require class attendance, the first semester of law school is going to be rough. If you’re living on your own for the first time in your life, the first semester of law school is going to be rough.

Regardless of your background, law school is designed to put you through a challenging gauntlet during the first semester. It’s designed that way, so if you’re one of my readers who is interpreting the challenges of the first semester of law school as a sign of prevailing personal shortcomings, please stop. It’s not you, it is the experience.

There are ways to structure your study time to get the essential study activities done. There will be other posts in the future about structuring time to preserve work-life balance and ensure the activities of daily living don’t take a backseat to study.

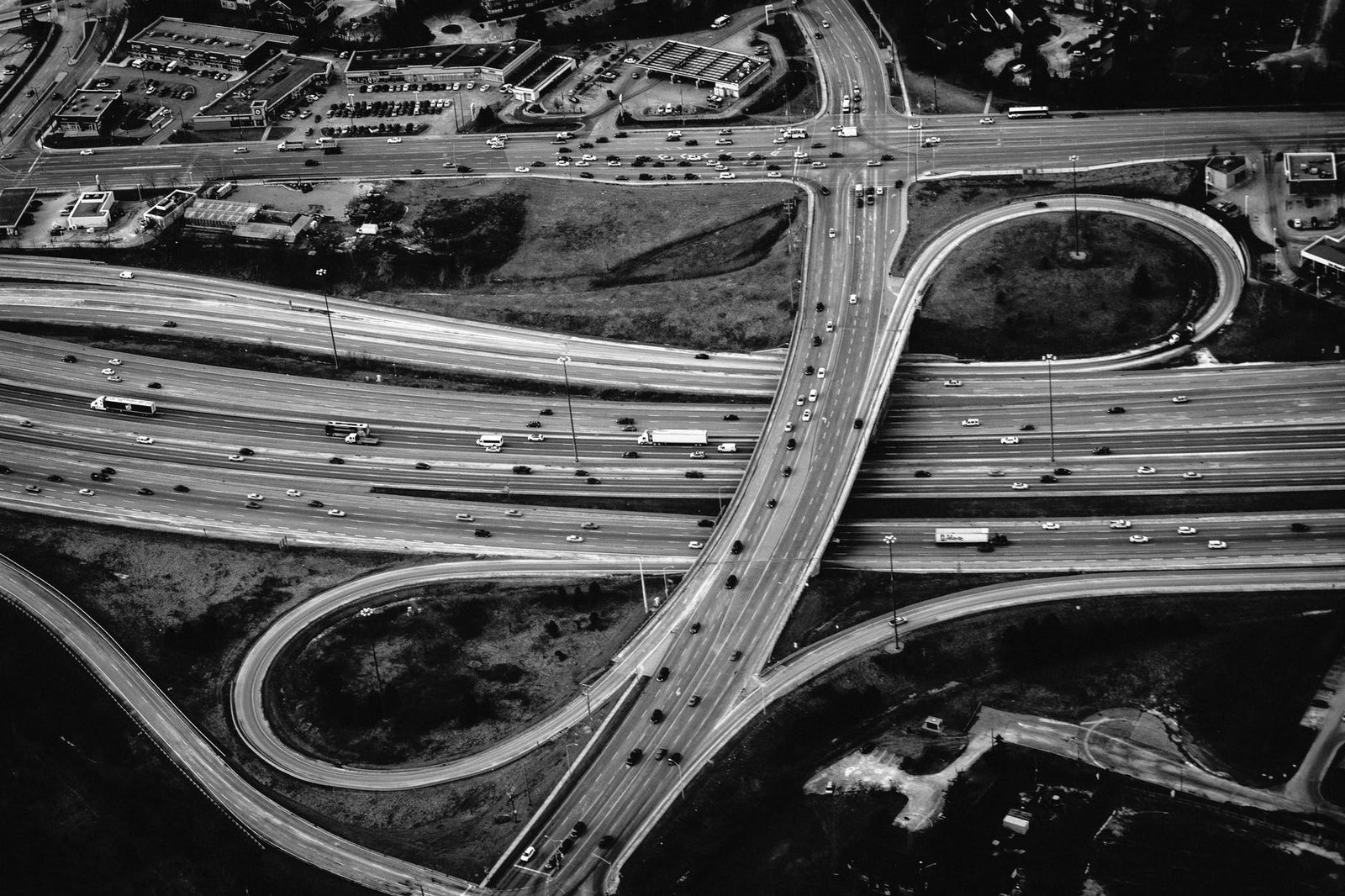

Stack activities in a sequence that helps your brain take the on-ramp and off-ramp from learning activities

There are activities and tasks you will need to perform on an almost daily basis. These include, but are not limited to, reading, taking notes & briefing cases, and attending class. There are other activities/tasks that will only happen once or twice over the course of the semester such as midterms, final exams, and writing assignments for your legal writing class. Finally, there are the activities that serve as the bridge between the near daily activities and the once or twice a semester activities such as outlining, reviewing, memorizing, and completing practice problems.

With a couple of small tweaks to your process, you can elevate reviewing and memorizing to a daily activity and then with some conscientious planning and scheduling, you can update your outlines and work on practice problems weekly. For those who are interested, I’ve used the principles of spaced repetition and self-testing to inform the crafting of this agenda; I’ll share more information about them and their peer principles, interleaved practice and environmental diversity, in future posts.

Event Agenda

Let’s begin by setting out a class-by-class agenda where we pair one study session and one class session together as an event:

During the study segment of the event:

- Start with a blank page (or document) review to practice recalling the material recently learned (3 to 5 minutes)

- Compare the contents of the no-longer-blank page with your class notes to see what you forgot (5 to 10 minutes)

- Review any lingering questions from your last work session to see if the connection appeared while your subconscious was playing with the material or you learned more things in other places (less than 5 minutes)

- Turn to reading and learning the “new” material you’ve been assigned following a protocol like the one I offered in Reading strategies for law students (45 to 60 minutes)

- Please note: During the first half of the first semester of law school it is completely normal to need 90-120 minutes per assignment (assuming 50 minute classes) since you are simultaneously working on vocabulary building, contextual schema building, and trying to learn causes of action, rules, elements, and application boundaries. As your vocabulary grows and your contextual schema is solidified, you will need less time to glean essential information out of reading assignments.

- After finishing the reading assignment, perform another blank page review to practice recalling the information you just read (3 to 5 minutes)

- Check reading notes and recall attempts to see what was missing. (3 to 5 minutes)

- Set learning goals/objectives for the class session this information will be covered in.

During the class attendance segment of the event:

- If possible, arrive 5-10 minutes early to class and review your goals and questions for the upcoming class period.

- While attending class, use this time to:

- Resolve any lingering confusion from the reading assignment

- Clarify or correct your understanding of the reading material

- Capture any “new” material your professor provides orally (including hypotheticals)

- Explore the application potential of the reading material to different factual scenarios

- ASAP after class:

- Take a few minutes to review your notes and fill in any gaps that you had to leave due to time constraints

- Identify the lingering questions you need to try to resolve during your next study session

- Scan syllabus or casebook’s TOC to see if you are continuing a long topic or shifting to a new topic with your next study session

Weekly recap

The law schools I’ve observed craft schedules so that most students are attending class four days a week and then have a week day free for review, work, or internship-type placements. So here’s some pointers for using that time to review and practice using the materials.

- Begin with a blank page review to see how much you remember from the prior week

- Compare your recalled document with the notes you took over the course of the week

- Identify the varied legal issues and rules that were covered in class over the week and record them in a document

- Some peoples’ brains prefer going from issue -> rule and other peoples’ brains prefer going from rule -> issues. It doesn’t really matter which way your brain works during the learning phase, you just need to capture both the issues and the rules from class in your exam preparation document.

- Regardless of whether you choose a “standard” outline, or a flow chart, or a mind map, you’re going to have to spend some time figuring out the conceptual relationships between the different legal issues you’re learning about in class. For example, to sue on breach of contract, plaintiff needs to establish there was a contract to breach, so contract formation material (offer, acceptance, consideration) generally needs to precede information about determining breach, calculating damages, and selecting remedies in your contracts exam preparation document. As another example, the group of torts called intentional torts require plaintiffs to allege intent, so your torts exam preparation document should note that in the absence of intent facts you may skip the intentional torts analyses and look into claims for negligence or strict liability, depending.

- Once you’ve denoted a path to travel between legal issues, use the facts from the cases you read and the hypotheticals your professor uses to illustrate where the lines live in “grey” zones between requiring use of one set of rules and requiring use of a different set of rules.

- Grab a practice problem from the appropriate chapter of your preferred study aids and see how well you can spot issues given a new set of facts, how well you can recall the rules, and if you are able to plug facts into the rules to see what outcomes ought to be.

- Identify questions you want to take to your subject-matter expert, i.e., the professor, because you haven’t been able to figure out the answer for yourself after 1) reading the assignment, 2) attending the relevant class, 3) reviewing the material and attempting to place into the big picture, and 4) trying to use in a practice problem.

As a usage note, the students I coach on this system say it feels very artificial for about two weeks, but once it becomes a habitual method to approaching studies, it seems to increase individual efficiency and reduce overall time required to achieve their learning and mastery goals. So if you try this, please commit to doing it for at least two weeks before throwing in the towel and trying something else.